A Christmas Speech / December 2023

Today

as we approach the end of another enumerated year,

as daylight only has its limited span

and sunlight is scarce,

as gluhwein stands and Christmas lights

are strung along the streets

and houses and shopping streets

are blazing with Christmas hits vol. 3,

while the radio reports the enumerated deaths of the people in Gaza,

still counting,

I would like to talk about childbirth and decapitation.

My fellow born womb carried critter1,

this is where we start today.

For, dear reader,

one way or another you were born

by which I mean that

prior to your first breath of air

you have spent a months-long period

unfolding inside another body2 on which you fed

which became part of you

and by which you were carried.

Now, in your presence

I would like to refuse

some concepts related to child birth.

CHAPTER ONE:

refusal of Birth as an Origin story:

origins do not exist

– a.k.a. your surroundings are part of you

Congratulations!

Against all odds you were conceived.

From a single cell

to a fully grown baby in just nine months.

Amazing.

You are a miracle. And so am I.

This fragment

is the beginning of a documentary called

Life Before Birth – In the Womb3.

It’s the intro,

as sketched by National Geographic

available on a YouTube-channel called Naked Science.

While I am generally appreciative of random nudity, I find this fragment to be an issue.

You,

at your very outset

appear enclosed

from the world around you

which is a hostile place

where you can only arise against all odds.

There is a tendency to think ourselves

as separate from our environment,4

a capital-letter I

that moves through a world,

which serves as the background for this big I.

It is only in pushing this world

to the background,

that our Origins can become miraculous.

I the Subject

in world the Object

am Amazing from the very start.

For what is to follow it is crucial to reject this.

For the sake of all earth-bound critters,

my friend, let us retell the story of your birth,

not as a hero against all odds

but as a biological story involving some nudity.

This is what I understand so far:

Your body, mind and soul,

grew out of material.

this material became you

the form, the content, the flesh

when it was lodged in a womb

and drew life supplies

from all through the body it was part of

which itself drew life

from the world it was embedded in.

Your life did not start

on a lone and epic journey.

You were allowed to grow

on the saps of the human you were part of.

Moreover,

you never did inhabit a human body

a body would be a stone cold thing

were it not joined to a head.

– my god! –

You grew out of a full person,

only becoming you in the process.

There was no you preceding this

and even at birth

you were not cut off.

When you came into the world

through a vagina

or cut from a belly,

you were carried and nursed and fed by many hands5,

or you would be dead,

as we know

for many have died.

Let us start

by acknowledging this simple basic stand:

your birth was not a miracle.

In the 1970’s

Adrienne Rich wrote a book titled:

Of Woman Born, Motherhood as Experience and Institution6.

I read it after having born a child almost 50 years later.

Now 50 years, is an eternity, right?

When we are talking about childbirth,

women’s rights,

human rights?

And this book had been written in the United States,

while I am a continent away

full citizen

of Belgium’s social-security-paradise, right?

I was struck

by how much I recognized of what she had written

and how little I had known.

After 50 years

I could still tie it

to my own experience of giving birth,

which was one of deep alienation and loneliness

– in part because

I had no framework to connect it to.

This is why 50 years later and an ocean away

I am glad to be able to quote Adrienne Rich

on finding resources

dealing with this strange phenomenon.

She writes:

In my father’s library,I stole glances at the thick red volume Williams’s Obstetrics, a textbook written by the Obstetrician who had delivered me. Nowhere was the face of a laboring mother visible in its photographs; all was perineum, episiotomy, the nether parts I recognized as like and unlike my own, stretched beyond belief by the crowning infant head.

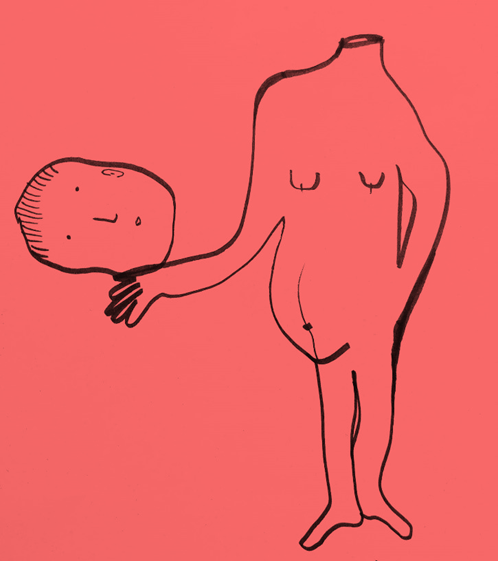

I find that discourses on childbirth,

and in particular

what counts as knowledge,

is still quite often

dismissive of lived experience,

starting with cutting

the mother’s head out of the picture.

What follows

is the recollection

of my two experiences of giving birth

during which decapitation

led me to identify with Christ,

that critter of earth

notoriously born on Christmas.

INTERLUDE:

on being Christ

My first pregnancy ended

in a last-minute cesarean section

which was very unsettling and overwhelming.

During this procedure

– which I lived through as a background,

the object if you will –

I was rolled into a room with a shiny white ceiling

giving me the exclusive opportunity

to see everything happening to my body

– that is to say, to me –

sharply mirrored above me,

even if they had put a sheet

between my head and the rest of my body,

this being the policy

to avoid me from getting too upset.

I hardly think the sight of my own body

is what upset me most at that point,

or that it is necessary

to avoid being upset in this situation,

and I strongly suspect

there was an unacknowledged aspect of facilitating

the work of the gynecologist as technician

urgently

and with precision

– the cut was complimented afterwards –

cutting out babies from their suffocating surroundings.

I imagine it can be unsettling when these surroundings have a head.

Failing to make eye contact or to be involved

with what was happening

I started to study my body in the shiny ceiling.

Afterwards,

I remembered

having had this thought

that I had looked like Christ in reverse

but I couldn’t really recall how that worked.

I just knew that I had thought it and that this thought

had given me joy in that moment.

Three years later

I was rolled into an operation room,

fully prepared for a C-section

that would deliver

baby number 2000 of the year 2020

Hospital Sint-Augustinus, Antwerp.

The atmosphere was overall jolly and as I had insisted

to be taken into account this time

there was no sheet between my head and my body,

only a mouth mask

slightly blocking my view but hey,

there was a pandemic

and at least there was no sheet.

And people were really nice so this mask

– it was a minor thing.

In an attempt to connect to my earlier,

more nightmarish experience of childbirth,

I was determined to seek out this Christ-like-image

and remember it sharply.

Here it is:

The outfit of the woman getting a C-section

is just a hospital gown which is slid up

so that you lie

bear belly, bear cunt, bear legs, and red socks

to keep your feet warm

which does disrupt the image.

The gown then functions like some sort of

badly positioned loincloth.

Your arms are spread for the anesthesia and really all you can do

to be involved in the whole process

is to look slyly in the direction of your nether parts

giving your head the suffering downward allure

of crucified Christ, only horizontal.

And you are not dying for humanity

you are birthing a human being.

And you are not starved

you are pretty much at your biggest ever.

And you are not wearing a crown of thorns

but a hair net and a mouth mask,

and people did not judge you to death

but are helping you in the most profound way you can imagine.

But,

like Christ

you have unwillingly surrendered your body,

and I don’t know what to do here remarking

that I feel closer to this hanging man on a cross

than to any picture of Mary

her clean devotion and invisible labor

an image to me irreconcilable with – what – life?

CHAPTER 2:

why and how this relates to you

a.k.a. it is a matter of politics, my dear

These matters relate to you

whether or not you have a uterus

and whether or not you are planning to use it for gestational purposes.

Truly, you do you.

My aim here is to point out

the societal significance of childbirth

as I feel it is not often taken into serious consideration.

Take warfare as the counterexample.7

Warfare is seen by definition

as a societal issue

– not personal, or interpersonal.

Wars bear weight, and stories.

Wars are what we learn about in history class.

They are tied up

with how governments rule

and how empires expand or perish and they are

in all their gruesome stupidity

a matter of politics.

They are a matter of politics to the absurd level

where bodies are to remain numbers under all circumstances,

not human beings who could be individually mourned or avenged.

Wars are topic of important thought

and in as far as they are

topic of important thought

it is deemed wise not to think

of the bodily mess they are soaked in.

Childbirth and gestation

while likewise prone to politics and societal narrative,

while having an enormous historical and current death toll,

are seen as private matters.

If they do appear as a topic in history class

it might be in the form of China’s one-child policy

as an example of faraway cruelty

where politics got too involved in personal life.

This framing too,

I would like to reject.

Childbirth,

it’s when and how,

it’s how many and by whom,

the stories of its beauty,

the stories of its horror.

All of this is politics.

Childbirth is foundational to any form of society.

It is the bodily process through which life rambles on

and continues to produce

imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy8

one baby at a time.

That’s an uncomfortable frame, right?

I took this phrase

imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy

from bell hooks.

She wrote

that whenever she calls it out in full length

it makes her audience laugh.

And, when I read it,

it did make me laugh.

And then, she goes on to ask why it makes us laugh,

when it is an accurate description of the conditions we live in.

I repeat the sentence here,

because I understand these are also as the conditions

I live in.

And though we may like to imagine childbirth

as an apolitical, “natural” realm

– these are the conditions

under which people bear children

– and they work straight up

into the delivery room.

This text is not feminist because of its topic

– as said, childbirth relates to all critters,

but it is feminist in its ethics.

Here is bell hooks again:

To me feminism is not simply a struggle to end male chauvinism or a movement to ensure that women will have equal rights with men; it is a commitment to eradicating the ideology of domination that permeates Western culture on various levels —sex, race, and class

Shit.

I guess what I am talking about is a manifestation

of this ideology of domination

and how

– through the experience of childbirth –

it got shook up.

CHAPTER 3:

narratives that haunt us

So let us think for a moment about narrative.

I would say that there are two prevailing narratives

enclosing the pathways to understand birth and gestation

as a matter of public significance, and they are, roughly,

the two ways in which I know people make sense

of the experience of childbirth.

There is a narrative that all is nature.

It goes something like this:

like all animals, women can give birth

childbirth is beautiful and natural let us embrace it

and rejoice in our female strength.

This is a narrative that is easy to pick at

in the sense that it is quite often mocked

even if it has helped people

to find some agency in childbirth.

I am wary of it,

in its connection of the female to the animal

(or alternatively, to the goddess)

and in that I fear it to lead to feelings of failure

when births do not go smoothly.

But this has never been my narrative

and I am not going into it here.

Rather

I would like to take a swing

at a narrative that was my own,

and that is in dire need of some critique.

It goes something like this:

In history, a lot of women

died in pregnancy and childbirth

because health care was bad,

because so little was known,

because of stupid superstitions.

Knowledge has increased

with the advent of a Scientific Approach

and child birth is now good and safe,

in as far as countries are rich

and have good health care systems.

This is the framework I was brought up in.

It was, in broad strokes, what I believed in

when I went into the hospital to give birth

to the first child that grew in my womb.

It was a narrative that suited and comforted me.

After all,

I lived in a rich country

with good health care

– science and doctors would deliver this child

and I could rest assured

and in truth,

I didn’t want to be bothered

with the vaguely pink prenatal yoga-brochures

that made me want to vomit then

and still trigger a sense of revulsion.

I felt belittled

by their yogi-tea tone of writing

and, sailing on the confidence of my privilege,

I didn’t even want to look any further.

Thank god!

For of course I deeply distrusted

the idea that any knowledge or learning

could happen through the body.

It was a time when I thought

I could never learn how to sing.

This narrative, has turned out, to be rather stupid.

So I reject it.9

First of all,

I refuse its reduction of history

to a linear narrative of progress.

While I do not deny the positive impact

of evidence-based approaches to childbirth,

there is more to be said.

At the outset of gynecology

as a legitimate scientific discipline,

a lot of women died in childbirth.

There was no gradual and linear improvement

but rather a peak in deaths.

Capital S – Science

as an area of Men and Heads

excluded female practitioners from the knowledge it gained.

I do not forget that only one generation ago

my mother was taught philosophy

by a man who felt and shared that

university is not a woman’s place,

after which he addressed

all women dressed in pants

with a denigrating ‘meneer’, ‘sir’.

My mother does not tell this story

with pride of having overcome but still connecting

to shame and humiliation.

It was Science that looked down

on the knowledge and practice

of the women who had experience with childbirth

by doing and seeing it.

The split in the profession between midwives and gynecologists

has been ‘wasteful and disastrous’ (that’s Adrienne Rich again).

Let me quote her very clearly:

The midwives’ ignorance of the progress in medicine and surgery, on the one hand, and the physicians’ ignorance of female anatomy and techniques relating to childbirth on the other, were not inevitable. They were consequences of institutional misogyny.

This is where the system that now regulates birth originates.

And the professors,

who taught the gynecologists practicing today

were taught by

the same generation of professors who taught

my mother to shut up.

I would argue that to this day

knowledge of the body is obscured and ridiculed

not only in countries far away but right here, right now.

There is more than one way to obscure knowledge,

as the many paths of patriarchy have often shown us.

Making derogatory remarks on bodily experience is one of them.

Try talking about birth pains

as source of strength,

as inspiration for agency

and see whether you are not immediately shamed

into irrational hippie-hood.

Here is a game

to play at Christmas dinner, preferably at the point

where most food has been eaten

and people sit heavily around the table

– when catching up with each other’s life is over

and we enter the world of fun facts.

Get everybody a crayon and a piece of paper

and give a simple assignment.

Draw me a clitoris.

Get beyond the point of scoffing and of maar allez

and say: seriously, draw me a clitoris.

Reassure them that a clitoris can range

that a sketch is never reality,

so don’t worry just try.

Up until very recently,

long after I actively

started to enjoy my clitoris

long after I gave birth to my first child

I could not do this.

Let alone that I knew

the size of my ovaries or my womb.

And if you play this game,

I wonder what you will get.

Also, make a note that this is not about

understanding the female body but the human body.

Out of all human bodies approximately half

will have a clitoris.

I still associate the gynecologist’s office with

being shushed and kept dumb

so as not to be a disturbance.

Our family doctor,

a young woman herself

will not help me out with a spiral

as she does not think it is part of her job.

Have a specialist see to your obscure regions.

While giving birth,

a training female gynecologist

(who has only just begun her professional life)

assured me – to my face – not to worry

then went into the hallway to call her superior

a bit too loud saying:

things were going bad could he come right away?

A nurse and a midwife looked at each other and went out.

Later on, the midwife came back

and let me hear the child’s heartbeat.

CHAPTER FOUR:

back to the data

When writing this text

I was looking up maternal mortality rates.

A page is devoted to these numbers on: ourworldindata.org

an open-source website stating as its mission:

“Research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems.”

Its page on maternal mortality starts with the following sentence:

“What could be more tragic than a mother losing her life in the moment that she is giving birth to her newborn?”

What I hint at,

is that there is a common logic undergirding

my own alienated birth experience

and the expendability of “mothers”.

Mothers losing their life are framed as a tragedy.

I am saying that

this is not what is at stake.

Human beings losing their life

through obscuring bodily knowledge,

is not tragedy.

It is cynicism.

There is a great disparity

when looking at maternal mortality figures.

Ourworldindata goes on and says in big letters:

“If we can make maternal deaths as rare as they are in the healthiest countries, we can save almost 300,000 mothers each year.”

This is not something to take in lightly.

I am quite sure that, depending on

time and place in history,

the birth experience I had –

Well, I would probably have died of it.

And I am quite fond of living.

If we identify people who die in childbirth

in faraway countries

as tragically lost mothers,

this does not serve

as a means to question and eradicate domination

on the basis of sex, class and race.

And it is this domination that makes people

who die in faraway countries dispensable as bodies.

A strange narrative of just domination

is reinforced by numbers

– still counting –

as scientific support

to a feeling of global superiority.

If all countries

could be more like ours

– casually ignoring that our country,

like a baby, really,

did not arise in a vacuum

but in close, parasitic relation to the world.

The logic of domination

that denies a person giving birth

the right to know

what is happening to them and to engage with it

is the same logic

that – in its grimmest results can ignore or dismiss

the dead bodies of others

in this great tragedy that is

imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

I would like to fix this.

I would like to solve all of this.

But acknowledging that I am a critter

I cannot believe in miracles.

This is not a source of despair.

There is hope in this knowledge as it makes clear

that we are never alone in making efforts,

in telling different stories

against loneliness and alienation.

This text too is not alone.

Browse through the footnotes, and see the references it builds on.

I am very glad to have shared these thoughts with you.

Thank you for reading!

Merry Christmas.

EPILOGUE:

dIALOGUE WITH A CRITTER BORN FROM MY WOMB

Dit is het ziekenhuis waar ik ben geboren.10

Ja, dat klopt.

Vertel nog eens.

Over toen jij geboren bent?

Ja.

Wel, jij zat in mijn buik.

Jij zat daar al lang,

was daar aan het groeien

en toen je groot genoeg was

en sterk genoeg

moest je eruit.

En dan zijn je papa en ik naar hier gekomen.

En dan duurde het heel lang.

Maar je bent eruit gekomen,

nu ja,

de dokters hebben je eruit gehaald.

En je had veel haar en je was heel schattig.

En toen kwamen mami en papi en oma en opa?

Ja, toen kwamen die kijken

en er waren dokters en verpleegsters,

heel veel mensen.

En toen was je heel blij dat ik er was.

Ik voelde heel veel.

- critter is a word I first encountered in Donna Haraway’s Staying with the trouble.

It comes up already in the introduction: […] mortal critters, entwined in the myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings. Or, as in the footnotes: critters refers promiscuously to microbes, plants, animals, humans and nonhumans, and sometimes even to machines.

I would suggest beestje as its translation in Dutch

↩︎ - Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born, Motherhood as Experience and Institution, the most referenced work in this text. I took and adapted from the foreword: The one unifying, incontrovertible experience shared by all women and men is that months-long period we spent unfolding inside a woman’s body. I much enjoyed the image of this unfolding, cutting out woman as I felt it made the sentence unnecessarily conforming to an outdated gender-binary.

↩︎ - Sophie Lewis, Feminism against Family, Full Surrogacy Now. Both the documentary fragment and the refusal of miraculous growth autonomy are taken from this book, which has been very inspiring and thought-provoking. You can find the original reference at the outset of chapter 3, ‘The World’s Oldest Profession’.

The title of this speech too was directly inspired by this book, which also provides a lot of clear information about the physical process of gestation, starting its Introduction with the glorious sentence: It is a wonder we let fetuses inside us. Now, other than what the title and this sentence might suggest, I find its ethics and politics heartwarming, and generous, advocating for another kind of kinship: The fabric of the ‘social’ is something we ultimately weave by taking up where gestation left off, encountering one another as the strangers we always are, adopting one another skin-to-skin, forming loving and abusive attachments, and striving at comradeship. (from the introduction of Feminism against Family).

↩︎ - Lisa Doeland, Apocalypsofie. This book too has been a great source of inspiration in writing this. of the concepts foreground/background, relating to human/earth can be found in chapter 3: ‘De vele stemmen van Gaia’.

↩︎ - Judith Butler, Frames of War, introduction: ‘Precarious Life, Grievable Life’

On p. 14: It is not that we are born and later become precarious, but rather that precariousness is coexistensive with birth itself (birth is, by definition, precarious), which means that it matters whether or not this infant being survives, and that its survival is dependent on what we might call a social network of hands.

↩︎ - Adrienne Rich, same book, chapter VII, ‘Alienated Labor’.

↩︎ - Judith Butler, Frames of War, introduction: ‘Precarious Life, Grievable Life’,

Butler describes frames and how they may be troubled by “something that does not conform to our established understanding of things.” It is not that there is no bodily account of war – the testimonies and photographs obviously exist, but war terminology/strategy/politics and testimonies from warzones are often at odds. In the intro I spoke of Gaza (which is not strictly a war, but a genocide in occupied territory). There is a conflict between the images and testimonies we have of people in Gaza and words like ‘measured response’ and ‘proportionality’, which seem to operate in separate realms, even if they are printed on consecutive pages in the newspaper.

↩︎ - bell hooks, The Will to Change, chapter 2: ‘Understanding Patriarchy’.

Often in my lectures when I use the phrase “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe our nation’s political system, audiences laugh. No one has ever explained why accurately naming this system is funny. The laughter is itself a weapon of patriarchal terrorism. It functions as a disclaimer, discounting the significance of what is being named. It suggests that the words themselves are problematic and not the system they describe. I interpret this laughter as the audience’s way of showing discomfort with being asked to ally themselves with an antipatriarchal disobedient critique. This laughter reminds me that if I dare to challenge patriarchy openly, I risk not being taken seriously.

The later given definition of feminism is from Ain’t I a Woman

↩︎ - Adrienne Rich, same book, chapter 6 ‘Hands of Flesh, Hands of Iron’, describes the history of this separation of the profession between ‘midwives and obstetricians’.

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch. Though not directly referenced here, its reading has informed my understanding of the situation as a construct rather than a “natural” evolution. I think especially of the chapter titled: ‘The Accumulation of Labor and the Degradation of Women: Constructing “Difference” in the “Transition to Capitalism” ‘. – Great use of quotation marks in this title.

↩︎ - This is the hospital where I was born.

Yes, it is.

Tell me again.

About when you were born?

Yes.

Well, you were in my belly.

You had been there for a long time,

you had been growing.

and when you were big enough

and strong enough

you had to get out.

And then, your dad and I came here.

And it took a long time.

But you came out,

well, doctors got you out.

And you had a lot of hair you were very cute.

And then, mami and papi came

and oma and opa?

Yes, they came to see you

and there were doctors and nurses,

a lot of people.

And then you were very happy?

And then I really felt a lot.

↩︎