A Labor Day Speech / May 2024

Hi

and welcome to the written version of our Tiny Demolitions’ speech of May.

This piece will consider: labor, value and – yes? yes. – it will consider the soul.

But first!

A sidenote on stories as they are talked about in these pages.

Tiny Demolitions sets out to deal with stories. Stories, not as epic plotlines, but as part of our tract of thought and feeling. We care about stories in the way they shape our horizons, the way they inform how we can exist, or, potentially, how we cannot. It is through stories that we can imagine – in a flicker! – a good life, a good person, a healthy family, hard work.

Really, all of this shit.

We believe there is work to be done in understanding which narratives shape us, and how, to not take them for granted or as natural1, and to continually inform them with our lived experience, and the lived experience of others whom we can – yes, oh, yes ! – learn to attend to.

CHAPTER ONE:

the Soul and Hesitation

I hesitate in writing

and speaking about the soul,

the very word

seems to come with a warning.

And I think this hesitation

is two-fold.

FOLD 1: TEMPORALITY

I am talking to you

from the month of May.

On May the First

we had the international celebration

of Labor Day

de Dag van de Arbeid

which can remind us, at its best

to think about tangible, pressing issues like:

working conditions

care as labor

and the ongoing exploitation

and destruction of huge swaths

of the living world.

To move our thoughts, then,

– to thinking about the – eh –

soul

something, seemingly, out of this world

something unclear

something

my parents had already classified

as catholic bullshit

from which they had rightfully

rid themselves

– well, this can cause some hesitation.

Nevertheless, I want to go on

precisely because I think

the story of the soul got lost,

when we might need it.

That it was made

intangible

and elusive

out of this world

and so hard to even consider

when at the same time

through the perpetual

crises of our capitalist

world order

– sometimes it feels

like my soul hurts.

How could it not?

So I am writing and speaking about the soul

and it would give me great pleasure

if you could bear with me.

FOLD 2: DISCLAIMER – LOSING THE SOUL

I grew up

without a soul

– that is to say

without any concept

of a soul

and without any thought

about it.

My father,

born in 1948

in the small town of Lier, Belgium

had a teacher

at the age of 6,

and for each of his pupils

this teacher had put

a white piece of paper on the wall,

and on this piece of paper

he had drawn a heart.

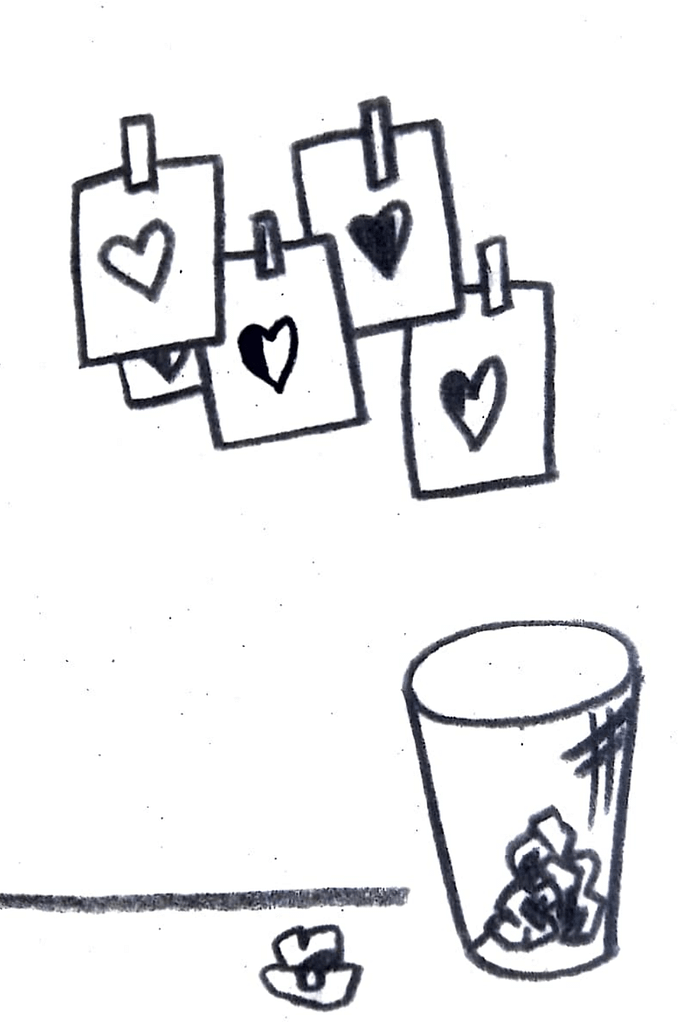

Dit, kindjes, is jullie ziel

This, he said, is your soul.

And every time

they did something wrong

there would of course

be physical punishment

which was a given at the time,

but in addition

he would color

part of that white paper heart

black

to show the stain sins left2

on these 6-year old’s souls.

My parents grew up

undergoing weekly pastor’s preaches

filled with looming doom.

They connect de ziel, the soul,

to words like zielenheil

which implies salvation

and thereby also the alternative

of eternal burning.

They learned to connect de ziel

to lonely fears

in the dark,

hidden under their blankets.

Fears of the devil

lifting them from their beds

as they attempted to sleep,

their bodies vessels of sin

tiny, weak and fragile,

their young souls stained.

And all of this

they learned to shed –

as they grew up

when society

seemed to grow away from catholicism,

the influences of priests and devils waning.

And while their mothers

still went to church,

they learned to tell themselves

it wasn’t true

so they could sleep.

And the devil

would not come and get them.

And they were not filled with sin.

it wasn’t true – it wasn’t true – it wasn’t true.

They gradually left the soul

for what it was

and went on with their lives

and made some progeny

because ga en vermenigvuldig u,

go forth and multiply,

was part of “a good life”

and so I grew up

with parents who thought and felt

#parentsarepeople

but there were no stories

about a soul.

And you see

how this can lead

to some hesitation

– I do not wish the soul

of my parent’s childhood

upon anyone.

But that does not mean I want to give up on the soul altogether.

CHAPTER TWO:

Value and Labor

Waarde en Arbeid

Let me go back, briefly

to de Dag van de Arbeid

and with it to the concept of value.

I think what de Dag van de Arbeid

reminds us of mostly

is the “value” of labor

which needs reminding

because it is quite often

devalued, in terms of money

and paychecks that vary

from barely sufficient to non-existing.

And through this reminder

that labor is nonetheless valuable,

we are reminded

of the value

of those who do labor.

I understand the need

for continued and increased attention

to working circumstances

in a capitalist world

that drives on exploitation and extraction

and I support

all commemorations

of social action.

And yet,

there is something uneasy

about this celebration.

There is something uneasy

in the assumption,

that what is of value

is that which makes an economic contribution,

that which makes the world go round,

which is, and I quote Sophie Lewis3 here:

“nothing much to be proud of,

given the state of the world.”

Moreover,

there is something sad

about this step in between

die tussenstap

– that we would only value

those who labor

through their labor

rather than

valuing people

for just – being alive

– acknowledging

that life going on

is valuable in itself.4

CHAPTER THREE:

The Unaffected Realm of The Family

– the Sorrow of Motherhood

This is the point

where I turn to my mother

who is the person

who took on

the re-productive labor

the never-ending feeding, washing,

playing and comforting5

on which I grew.

To say it unfaithfully with Karl Marx

She mixed her labor

Marx in Gilmore in Bhandar & Ziadah (ed.).

with my earth

and in so doing

changed me

and herself alike.

Kind of.6

She did this

without any breaks

and fully within the narrative

that the world was harsh

and home would be our refuge.

And I believed this

even though

my always busy mother

was haunted

by spells of depression

that later turned

into seemingly random

outbursts of rage.

My mother believed

not in a soul

but in the sacred story

that through my children

I find happiness

Goddank heb ik jullie nog

thank God, I still have you,

even if the daily reality,

and experience,

the endless work of the house

and the built-in loneliness,

betrayed this story.

She had ingrained that this experience

did not hold knowledge

and that it didn’t matter

The very reasonable frames

with which she had modeled

her life

– a house, an income,

a family –

had been procured.

She was supposed to be safe.

Her sorrow

did not tell her anything about the world

– it only meant she had failed –

And added the layer of guilt

that kept her going

tired but endlessly

CHAPTER 4:

Frames that Matter

There are frames I had learned

to think with,

frames I thought mattered.

First and foremost

I wanted to be reasonable.

Reasonability was the only

way in which you would be taken seriously.

Religion was stupid,

again, we only did Reason

and this made us smart

or it made us at least smart-er

than others,

whom we could talk to

but not really listen,

because they were not

quite as reasonable as us.

Ethics were tricky

and only to be discussed

in material terms

– Marx, yes, Jesus, no,

Audre Lorde, who is that? –

And if you talked too much

about ethics

you would have to watch out

because the world

as it was

– and honey, you cannot change the world –

was organized

according to the principle of self-interest,

people care mainly for themselves

– so you better organize your life

to protect yourself

from the harm that comes

from the self-interest of others.

Being too kind, means you will lose

and you will not be safe

– and to understand

what it means to not be safe

just turn on the news,

or glance7

at the people who live in the streets.

Don’t look too close,

you need to learn to ignore

– just long enough

to understand that there is danger

and you need to be safe.

So get a house,

get a family

and get a job.

And you will be safe.

The life of my mother

did not make sense

according to these parameters.

The promised safety

seemed transformed

into daily torment,

and by the time I was a teenager

I knew very well

that my mother

did not enjoy life.

The status of the emotional framework

in all of this

was unclear.

I experienced emotional warmth

– yes

and in my family

there was a tendency towards kindness

– yes

But it sure had its limits.

I remember being a rather fierce child

and sometimes

getting the label

hysterical.

I think overall

anger was not appreciated

in particular for me and my mother

as we seemed to fall

on the girl-side of the family.

I still

don’t know how to do conflict.

The idea that emotions

could hold information

would have been met

with seriously raised eyebrows.

In this way, it seems

like there was still some catholic remnant8

of passions needing to be controlled

in order to grow

as a human being,

which now might not mean

be virtuous,

but rather, be functional.

And this view of emotions

which I would call

reluctant recognition

got tied to medicalization,

for many people in my family

suffered from depression

and other psychiatric disorders

So the general advice was

– beware of emotions

they are treacherous

and they might hurt you

so cultivate reason

and you might be safe

and know when to medicate.

And all of this

I learned

with its great focus

on Reason and Safety

and I was truly great

at being very reasonable

but I did not know when to medicate

and crashed very reasonably

into depression at the age of 20.

Brace yourself: we are getting towards the soul.

CHAPTER 5:

We are getting towards the Soul

I had therapy, and medication

like so many people

living in Belgium today

and to this day

I am still on a daily dose of duloxetine

have been for about ten years

and as long as it helps me

to be alive to my fullest extent

I don’t plan to quit it.

I am not interested

in living my pure natural self

truly

I don’t think it even exists.

But up until recently

regardless of the emotional work

I did in therapy,

regardless

of the close analysis of my nuclear family

and the pharmaco-remedy

that restored my

neurotransmitter-balance,

I could still be haunted

by shame and guilt

and loneliness,

not as a response

to a particular situation,

but as an existential

layering of my experience

that resurfaced on a regular base.

What I am getting at

is that the frameworks I was brought up in

did not hold up

to take into account my lived experience

and it haunted me.

And this persisted

even when I was

quite well-read in feminism

in politics of social justice.

Even if I had learned to believe

and defend,

that my anger was a good thing,

which it is:

#angerangerroar

Hold on.

I don’t want to brush over this.

When the frameworks you have

the ways you think

about what matters

and what does not

when these frameworks

do not take you into account

– your lived experience

when they do not take into account

the lives of people you are close to

and whose wellbeing affects you

– then you might want to question

these frameworks,

and reading about feminism,

and social justice

can help you do that.

Let me be very clear here,

we are part of a world

in which not all lives are equally valued

in which many lives

are actively forgotten

and ignored.

It took me

a lot of reading, and listening

to understand that

when so many lives are ignored

in our accounts of history

as well as in our expectations

of daily life, of “a good life”9

this does not only

do active violence

to those who are ignored

it means these stories themselves

are based on ignorance.

Ignoring so many lives

harms our understanding of the world

and through it

it makes it harder

for everyone

to live.

I quote bell hooks,

I think I need to do that every time,

she points out

we live in “white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy”,

and that we need this heavy phrase

to keep reminding us of it.

That this is not a natural state

but that it has grown

through a shitload of violence

by states and corporations alike

effacing lives and experiences

communities and species.

Its continuation

is premised on ideologies

of separation and domination

which define our reality

and still run

through our bodies, houses and streets.

This is knowledge that needs to be taught.

It is knowledge

that has brought me a lot,

not in the least

the solid ground

that my experiences

are connected to the experiences of others

– that I am not alone

– and that when I struggle

to live in the conditions

set out by white-supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy,

my struggle does not mean

failure

It does not mean

I am doing something wrong.

This isn’t true.

it isn’t true – it isn’t true – it isn’t true.

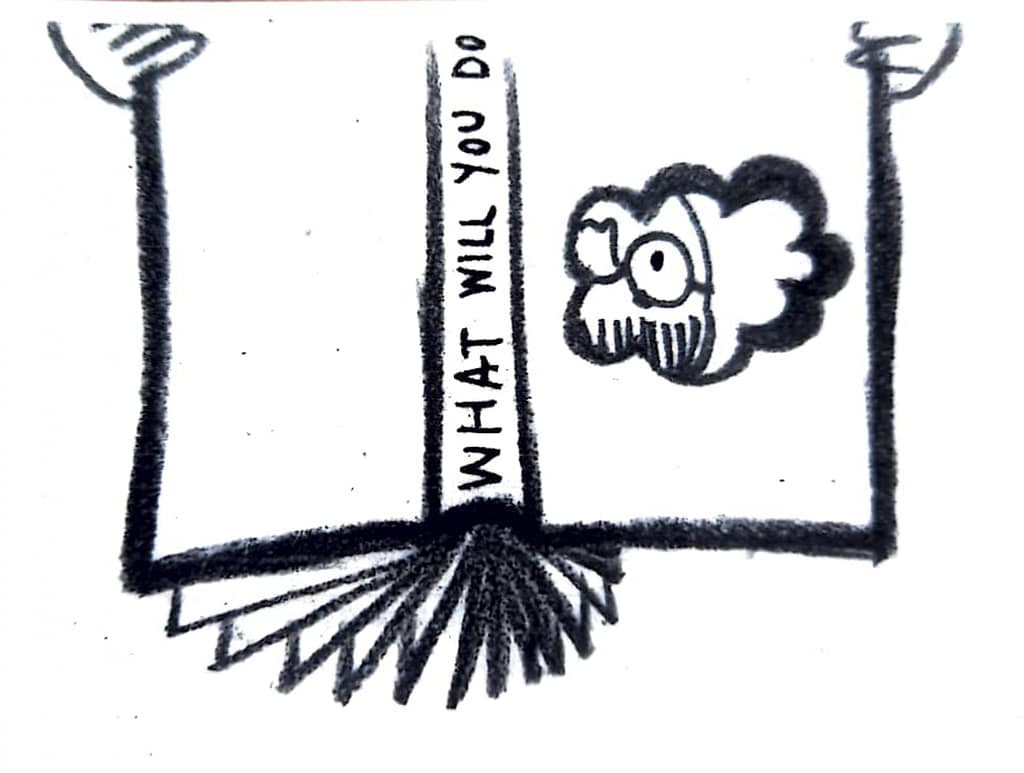

I think what changed

for me to feel less guilty

less inadequate

on an existential level

is not that I gained knowledge about the world

though knowledge is important

– I did not analyze my guilt away

and in all its overwhelming misery

knowledge of the world,

can be a straight line to burn-out.

What will you do with all this knowledge?

And this is the point

where something changed.

Something changed

in my position towards knowledge

that allows me to acknowledge sorrow

even when I am unable to fix it.

I will not fix it.

I am not outside of it.

And I think this helped my soul.

It helped me to stop running and crashing

– running had never been my strength, anyway.

It helped me to regain loving relations

with the people I am connected to.

In an interview,

Sylvia Federici said:

through my engagement in the women’s movement,

I regained my mother.10

I have a similar experience

of regaining my mother

not as a flawed representation of iconic motherhood

but as a person

close to me

in the world I am part of.

I think my change in position

resembles

something Veena Das has described.

She is an anthropologist

and she talks about the difference

between ‘knowing’ and ‘acknowledging’.11

Knowing has an assumption

to resolve something

and be done with it.

Acknowledgement

requires something else,

an ongoingness,

a relationship,

“a repeated attention

to the most ordinary of objects and events.”

I think this slow, gradual shift

allowed me

– don’t hesitate –

it allowed me

to be part of the world

to be affected by it

and to take that seriously.

When my mother

experienced the sorrow

of the lonely construction of motherhood

– and blamed it on herself

I think she missed a frame of reference

that could connect

her back to history

and the living world

– and it hurt her soul

And as I am permeable

and built with her labor

I feel this pain too.

In what I have told you today

I wanted to talk about the soul

as an intervention

in a logic of self-containment

that does not exist.

The soul

in this story

refuses the idea

that anyone could thrive

on the principle of self-interest

as it does not acknowledge

that anything like

enclosed self-interest

could exist:

there is no self

served by separation.

To attend to the self

and to attend to the world

are interlocking projects12

and attention for our primary caretakers

is somewhere in the mix.

I am so glad we made it here.

Thank you for reading

and bearing with my thoughts

incomplete as they are.

ADDENDUM

I know this speech draws heavily on the nuclear family. I hope it is clear, I do not want to celebrate this structure. The way I see it now, is that the nuclear family and its story are very much part of the problem. The promise they entail, of emotional well-being or of protection against loneliness, are betrayed by most people’s daily experience, not in the least that of women and children. I want to acknowledge these experiences – not as something to solve instantly, I don’t want you to blindly abandon the people you care for. But I do think there is an awareness, a sensibility, or a consciousness – you see how my vocabulary still rambles – that matters. It matters for your soul, which is entrenched in the world. Since the nuclear family is the structure I have always lived, I take its sorrows seriously, and hope that we can – yes, oh, yes! – train sensibilities together. So

that different possibilities can emerge.13

- First Footnote!

“But was there ever any domination which did not appear natural to those who possessed it?” In The Patriarchs, Angela Saini opens the first chapter ‘Domination’ with this quote by John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill. It is a quote from 1869! Just to get us started. At the end of the chapter, Saini writes:

When we settle for resting the case for ‘patriarchy’ on something as simple as ‘biological difference’, when the evidence points to a reality that is far more complex and contingent, we lose the capacity to see just how precarious it might be. We stop asking how it works, or the ways it’s being reinvented. We don’t dissect the circumstances that might help us undermine its ideological power right now. The most dangerous part of any form of oppression is that it can make people believe there are no alternatives.

I add the following sentence by Amade M’charek, quoted in Black Afterlives Matter (essay by Ruha Benjamin). It does not express the exact same thing, but furthers the thought, and has been on my mind a lot: “The factness of facts depends on their ability to disconnect themselves from the practices that helped produced them.”

Ha, what great phrasing!

↩︎ - Here are two stories, relating to this stained-soul-heart, tangling into the present.

First story:

A friend who went through the Dutch immigration machinery, told me a story about his stay in an azielzoekerscentrum (azc). To live there, is to live in uncertainty, and fear of being denied access to the country you have sought refuge in. In addition to this continuous incertainty, there was the threat of the black dot. It was said, that if you “misbehaved”, there would be a sanction in the form of a black dot on your file, i.e. your file would be marked, stained, and it would harm your chances of being allowed to live in the Netherlands.

Second story:

My daughter, who is now 6, has no paper hearts on the walls in her classroom. However, as it is a school in which many kids are marked as children with ‘behavioral issues’, for each child, there is a traffic light – green, orange, red. Every day, kids start on the green light. When they misbehave, they go to orange. If the ‘bad behavior’ continues, they go to red. This does not mean eternal damnation of the soul – but they will not get a sticker that they. The stories have shifted, but the mechanism of punishment and rewards is still broadly used “for the child’s own good”.

↩︎ - From: Sophie Lewis, Feminism Against Families: Full Surrogacy Now.

The same argument is there made in regards to motherhood, which can sometimes be valued on the premise that mothers make an economic contribution to society, by supplying labor force / which they do.

The aim is not to praise gestation as an essential use-value. […] frankly, the fact that gestation “makes an economic contribution” or “makes the world go round” is nothing much to be proud of, given the state of the world. (I’m more impressed by contributions gestating might make to this world’s destruction.) No, making the labor of social reproduction visible – again, we Marxist feminists cannot stress this enough – is very much not an end in itself.

If you wonder about this “social reproduction”, see footnote 5!

↩︎ - I attended a public talk organized with Sylvia Federici and Territorio Doméstico. Territorio Domestico is a collective space for struggle and empowerment of women, mostly migrants and domestic and care workers. It was a great evening. What they all reminded us of, with great eloquence and joy, is that domestic work and care work is work that supports life, which stands in stark opposition to the industry of war, to prisons, to police aggression, and polluting, soil-depleting industries. To put value in what supports life – is not an abstract thing, and it is definitely not commonly held knowledge and practice among those who create policies and execute power.

↩︎ - Social reproduction and reproductive labor refer to all the work that goes into reproducing the labor force, making people productive members of a capitalist society. This involves a lot of care work and domestic work, but also an emotional aspect. Consider the following passage from Federici’s Wages Against Housework, as it goes into celebrating ‘Mother’s Day’. Great fun!

[…] from the viewpoint of work we can ask not one wage but many wages, because we have been forced into many jobs at once. We are housemaids, prostitutes, nurses, shrinks; this is the essence of the ‘heroic’ spouse who is celebrated on ‘Mother’s Day’. We say: stop celebrating our exploitation, our supposed heroism. From now on we want money for each moment of it, so that we can refuse some of it and eventually-all-of it

It is an article from 1975, which called for women to organize, which they did (try and google ‘wages for housework’).

In They Call it Love, Alma Gotby explores the emotional aspect of reproductive labor. From the introduction:

This book explores the construction of emotional needs and the material and subjective organization of labour that is necessary to meet them. […] Emotional reproduction includes the forms of work that go into maintaining people’s emotional wellbeing and their ability and willingness to continue to engage in capitalist productive labor.

↩︎ - Disclaimer: I never read Marx.

This is an altered rendering of an indirect quote by Ruth Wilson Gilmore in an interview in Revolutionary Feminisms ( Brenna Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah). It goes: “One of the formulations that I always found very beautiful is where he talks about how we mix our labour with the earth, and in so doing we change the external world and change our own nature. I think that’s a really beautiful thing. I also think it’s true.”

I agree. I also think it’s true and beautiful. And you see how my rendering is really very unfaithful, even to this. I added this motherhood-thing, reminding me also of this poem by Hugo Claus ‘De Moeder’, and I would not take too much advise from Claus on family bonds, but it opens with this phrase:

“Ik ben niet, ik ben niet dan in uw aarde.” or: “I am not, I am only in your earth.” I do think it is a beautiful poem.

↩︎ - On the organization of safe spaces and wasteland in the late 20th C. I read Feminism and the Anthropocene by Anna Tsing and Paula Ebron.

This article taught me a lot. Its content is still reverberating in my thoughts.

A fragment:

We explore how separations between “security” and “wasteland” structured postwar growth, giving shape to Cold War expansion. The dream of safe spaces from enemies and toxins (however impossible such safety) justified the classification of other spaces, with their resident people, flora, and fauna, as expendable. […] the regime of separation between safety and waste spaces was made through mobilizing race and gender. White nuclear families anchored imagined “safety” while communities of color were made available for sacrifice. (663)

At the least, I hope this works against the idea of the “natural,

nuclear family”. This article helps to make the politics of this story tangible, historically situated.

↩︎ - A friend reminded me that this thought goes back way further, can be tied at least into Antiquity, and this seems to me true, and reminded me of an article by Simona Forti ‘New Demons: Rethinking Power and Evil Today’, which I think might bring you to a more substantial exploration of the matter.

↩︎ - In the introduction of They Call it Love Alma Gotby writes:

Emotional reproduction creates a feeling of investment in the world as it is. We have emotional attachments to a particular notion of the good life – a normative way of life which seems to promise comfort and happiness. Our lives under capitalism are in many ways disappointing and continually create negative feelings such as stress, resentment, depression and loneliness. But we all have an attachment to particular ideas of what a good life should look like – one that often includes the very sources of harm. We often continue to aspire to these ideals of a good life, even when they continually let us down.

↩︎ - This is drawn from the interview Federici gave in the book Revolutionary Feminisms (Bhandar and Ziadah)

↩︎ - Veena Das. From the introduction to Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. From the section “Voice and the everyday” (p. 6-7)

[…] the question is not about knowing (at least in the picture of knowing that much of modern philosophy has propagated with its underlying assumption about being able to solve the problem of what it is to know), but of acknowledging. My acknowledgment of the other is not something that I can do once and then be done with it. The suspicion of the ordinary seems to me to be rooted in the fact that relationships require a repeated attention to the most ordinary of objects and events, but our theoretical impulse is often to think of agency in terms of escaping the ordinary rather than as descent into it.

↩︎ - Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. Again from an interview in the book Revolutionary Feminisms (Bhandar and Ziadah). Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is an Indigenous (Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg) artist, writer and scholar. Here she describes a concept of freedom rooted in Nishnaabeg intelligence, knowledge and practice. A sort of ‘relational or grounded freedom’. (I think grounded is a very good term. )

A sort of freedom that is an individual and collective practice, designed to promote the well-being and self-determination of both the individual and the communal as interlocking projects.

↩︎ - Ruth Wilson Gilmore in Revolutionary Feminisms (Bhandar and Ziadah)

So, consciousness, and conscience-isation, which is to say, to translate that word from Portuguese to English: awareness is not just a matter of information; it’s not a matter of facts, but of developing and pursuing things through a sensibility that shows a different possibility can emerge.

↩︎